When President Joe Biden proposed a new federal government budget last month, he included big increases in police spending. If passed by Congress, the budget would expand funding for the federal police by 10 percent and transfer tens of billions of dollars to local police coffers with the goal of “putting more cops on the beat” and delivering on Biden’s State of the Union promise to “fund the police.”

This growth in federal spending would follow similar increases in U.S. cities. Despite calls in 2020 to defund the police, most U.S. cities increased the percent of their budget devoted to policing in 2021. Officials in Washington, Denver, and Los Angeles have all expanded or are proposing to expand their police budgets. Even Austin, Texas, one of the few cities to dramatically cut spending in response to Black Lives Matter protests, has restored its police budget and then some, growing its law enforcement spending 35 percent to a record $442 million this year.

The purported goal of all this police spending is to reduce violent crime. New York City Mayor Eric Adams, for example, pledged to double the already considerable number of police patrolling the city’s subway stations following a shooting on the subway in Brooklyn. Earlier this year Adams said he planned to cut funding to most city departments except the NYPD.

But the crime-control benefits of additional policing are unclear. Some studies find that additional police officers—the lion share of any police budget—have no impact on violent crime, while others find they decrease it. Amid this uncertainty, some cities are exploring other, nonpolice efforts to reduce serious crime like violence interrupters, mental health responders, and cash transfers. These approaches are promising but have received only a fraction of the municipal and federal spending the criminal legal system has.

A new study out Thursday suggests all the new police budget growth is likely to do one thing: increase misdemeanor arrests.

For the study, my co-authors and I analyzed hundreds of U.S. cities and towns over 29 years, tracking how police spending and staffing correlated with misdemeanor arrests. We found the size of a city’s police budget and the size of its police force both strongly predicted how many arrests its officers made for things like loitering, trespassing, and drug possession.

The trend was clear: When cities decreased the size of their police departments, they saw fewer misdemeanor arrests and when they increased them, they saw more.

We also analyzed whether community policing changed misdemeanor arrests. Community policing, with its emphasis on building police-resident relationships, has been a popular reform for decades, and the president’s budget proposal mentions it prominently. During a visit to New York City in February to discuss how to address rising gun violence with Adams, Biden once again touted community policing as a solution to violent crime. “I don’t hear many communities, no matter what their color or background, saying ‘I don’t want more protection in my community,’ ” Biden said. We found, however, that misdemeanor arrest rates did not change after a city adopted community policing.

In other words, if community policing improved relationships with residents, it did not lead to fewer misdemeanor arrests. It was the amount of policing, not the type of policing, that influenced misdemeanor arrest rates.

Arrests for petty offenses are devastating for the people arrested and their communities. Even a single arrest makes a person less likely to stay in school school, be hired for a job, or obtain housing. The punishment of an arrest often cascades into fines, fees, and what legal scholar Issa Kohler-Hausmann calls “procedural hassles,” even in cases that do not result in jail time.

As with many policing outcomes, misdemeanor enforcement is concentrated in poor neighborhoods and in communities of color, exacerbating the racial inequity of their harms. In high-arrest neighborhoods, police officers also have a harder time investigating violent crimes because residents have grown distrustful of the criminal legal system and are less likely to cooperate in investigations.

If intense misdemeanor enforcement reduced crime, these costs might have to be balanced against the public safety benefits of low-level arrests, but study after study has found intense misdemeanor enforcement does not reduce crime. One study analyzed the effects of randomly dropping some misdemeanor charges and found people who had their cases dismissed were less likely to be rearrested over the next two years, suggesting misdemeanor enforcement actively causes crime.

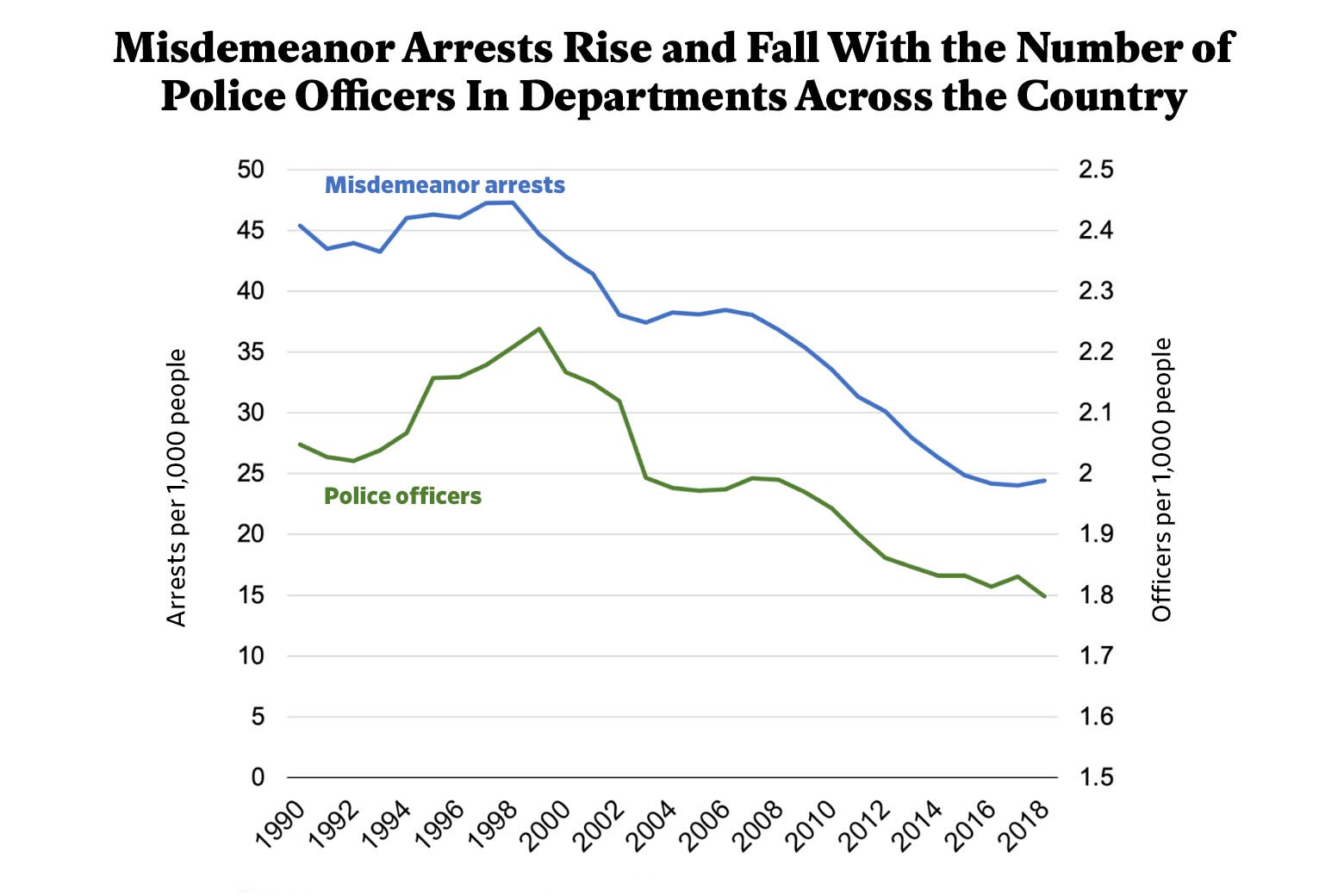

Misdemeanor arrests closely track the number of police officers active in police departments. The blue line in the graph represents the misdemeanor arrest rate across about 5,000 U.S. municipalities. Throughout the past three decades, it has closely tracked the green line representing the number of police officers. When local police in the U.S. were the most numerous, between about 1996 and 2000, so too were misdemeanor arrests. As police departments grew smaller through the 2000s and 2010s, low-level arrests shrunk, as well.

This trend demonstrates what police practitioners have known for a while. “When you hire more officers, they make more arrests,” as a former NYPD police chief put it.

Why arrests increase as the number of police increases is unclear. Our study could not determine why this is the case, but, as with any profession, employees likely want to demonstrate productivity. More police officers means each officer has more time to search people for drugs, look for publicly intoxicated people, or pull over drivers to administer breathalyzers.

Police have wide discretion when choosing whether to prioritize misdemeanor enforcement. The Supreme Court has granted police great leeway in choosing which laws to enforce, when, and where. If departments want to prioritize misdemeanor crime, they can, or if instead they put their resources toward solving violent crime, they can do that. Research finds that when police do the latter, they solve more serious cases. Our study finds that hiring more officers increases misdemeanor arrests more than it does felony ones.

Could it be that cities hired more police after they experienced more misdemeanor crime, and that explains the close correlation between officers and arrests? This inverse explanation is definitely possible, so our study compared the number of officers in one year with the number of misdemeanor arrests in the next to ensure it was not more misdemeanor crimes that were leading cities to hire more officers. We also used a statistical method called “instrumenting” to adjust for how more crime might cause more arrests. Even so, we found more officers lead to more low-level arrests, no matter how we sliced the data.

Our research also shows a significant but underreported trend: Police made almost half as many misdemeanor arrests in 2018 that they did in 1998. This large decrease in misdemeanor arrests has yet to receive much attention, perhaps because both progressives and conservatives perpetuate the myth that broken windows policing, with its emphasis on misdemeanor enforcement, has endured. The right’s love for “order maintenance” policing might prevent them from admitting that crime declined in the 1990s and 2000s even as police made fewer low-level arrests. Progressives might be loath to admit any improvement in policing, which this decline undoubtedly is.

As federal and municipal lawmakers increase funding to police, they should be aware of how doing so will likely increase misdemeanor arrests and their attendant harms. The typical police department only solves (makes an arrest in) about half of all reported violent crimes reported to them, so reallocating existing resources to investigating these serious harms is more likely to reduce crime than hiring more officers who will focus on petty offenses.

Amid a rise in violent crime, the messages of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests are being replaced by calls to hire more beat cops. Cities and the federal government are proposing more police spending, but the impact of all this new money is uncertain. One thing it is likely to do, even if paired with community policing, is generate more misdemeanor arrests. Arrests that will disproportionately hurt poor and Black people. Arrests that will keep people from jobs, housing, and welfare benefits. Arrests that will make it harder for police to investigate violent crime.

During this unique moment, elected officials have the opportunity to reach for innovative policing alternatives, refocus on violence rather than misdemeanors, and continue the beneficial decline in low-level arrests. Few seem ready to take it.